Picturegoer Vol. 3 Issue 20 - "Elio" (with "Bronco Billy", "In a World", "The Pirate", "The Trip" and Mel Brooks)

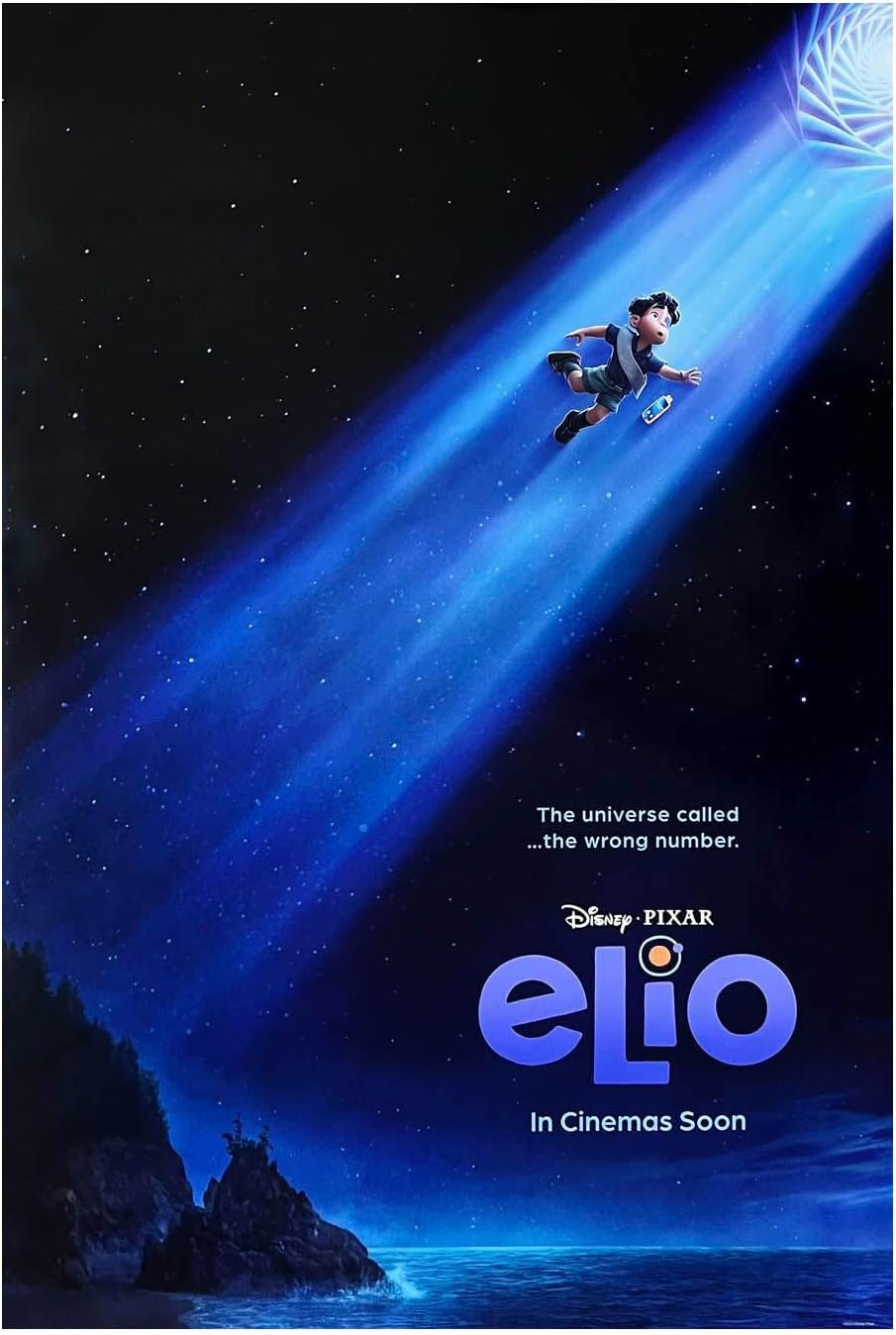

Elio (2025, d. Madeline Sharafian, Domee Shi, Adrian Molina) A lonely little boy dreams of being spirited away to the stars.

For what develops into a rambunctious science fiction adventure, “Elio” opens on an unexpectedly melancholy note. The film’s first scene introduces us to Elio (voiced by Yonas Kibreab) hiding under a cafeteria table, stubbornly refusing to interact with his Aunt and new guardian Olga (voiced by Zoe Saldaña). It’s shortly after Elio’s parents have died (the implication is that they were killed in an accident, but the movie admirably leaves their backstory ambiguous); this sweet little boy, with a charmingly crooked smile and wide, curious eyes, has become closed off, insular, uncommunicative.

While his Aunt is distracted, Elio wanders away from their table into a museum exhibit about the Voyager 1 spacecraft. As he looks up at a computer animated light show of expanding galaxies and endless possibilities, a single, astonished tear sneaks from his eyes, eyes that remain fixed on the Voyager 1 replica even as his Aunt drags him out of the exhibit. That same look will reappear from time to time throughout “Elio”, a reminder of the underlying, fundamentally existentialist questions that face the titular child protagonist: if this universe has dealt Elio such a raw deal, taken away the people who meant the most to him and understood him most deeply, what if he could simply leave this world and its problems behind…? We never forget the expression on little Elio’s face – both hopeful and heartbroken – as he began to contemplate the idea that we (the human race) may not be alone in the universe, and that he (a lost little boy) need not feel alone forever.

“Elio” is an animated descendent of the films made by Amblin in the 1980s, films like “Gremlins”, “The Goonies” or “Back to the Future” that appealed to kids but had just enough bite that those same kids could feel like they were getting away with something. When Elio finally is spirited into the stars, he meets aliens both friendly and fearsome; the movie’s main villains, a race of warrior aliens led by the bellowing Lord Grigon (voiced by Brad Garrett), are scary enough to pose a threat, but also silly enough to not give kids lasting nightmares. (There’s a sequence that recreates the old trope of having a villain shoot an underling to establish his baddie bonafides – Lord Grigon likes to do target practice with cute little flower-shaped aliens – but the payoff to the gag has a Looney Tunes quality that takes the sting out of it: the aliens survive being blown up, and instead just end up shorn of their feathers, embarrassed rather than annihilated). At one point in the second act, Elio is given a clone double who can act as his stand-in on Earth during his outer space adventures, and in the grand tradition of creepy movie kids, that clone is uncannily just a bit “off”; there are gags here (like one involving a set of garden shears) that would’ve given me proper but delighted shivers if I’d seen the movie as a kid, “scary” in a fun way.

“Elio” has a disarming child’s logic to its storytelling. When Elio is taken to space, the aliens he meets all looks like designs that could’ve been doodled in the margins of a child’s lesson book, and while the ostensible threat of the movie may be intergalactic invaders, what the narrative really boils down to is the ability to (in classic Disney terms) “be yourself”. Elio is mistaken for the “leader of Earth”, and is happy to go through with the ruse because it makes this previously ignored and ostracized child feel powerful and important; similarly, the “villains” turn out to be hiding their secret selves – encased inside fearsome looking metal mecha suits, the aliens of Grigon’s are actually soft, squishy caterpillar like creatures, putting on a big show – like bullies often do – in order to paper over their own insecurities. (Elio ends up befriending one of these little worm-like aliens – Glordon – and it’s quite remarkable how Remy Edgerly’s vocal performance and well observed character animation make this somewhat gross looking character incredibly endearing.)

“Elio” apparently went through a complicated birthing process; there are three directors credited here in two different places (Madeline Sharafian and Domee Shi are named right at the top of the credits sequence, while original director Adrian Molina’s name appears at the beginning of the ”secondary” credits roll), suggesting a production where creative teams had to be shuffled around like cards in a deck. (This, to be fair, isn’t the first such instance in Pixar’s history – both “Ratatouille” and “Brave”, for example, had late-in-the-day director changes.) Whatever the difficulties of the development process, they don’t show on the screen. This is a consistently delightful movie, one of Pixar’s best recent efforts, mixing together comedy, action and pathos with aplomb. **** out of *****

Bronco Billy (1980, d. Clint Eastwood) Charmingly slight Western comedy, with Clint Eastwood starring as “Bronco Billy McCoy”, the star and proprietor of a near-defunct “wild west show” touring then modern day (early ‘80s) America, who recruits a snooty heiress (Sondra Locke) to become part of his act.

Clint Eastwood has said many times that he thought of “Bronco Billy” as a Capra-esque comedy, gentle and good hearted; the titular character is basically an overgrown kid, prone to childish tantrums when he doesn’t get his way and believing whole heartedly in the idea of setting a good example for the “little pardners” who show up (in decreasing numbers) to his rodeos. All of that stuff works well; what works rather less well are the labored mechanics of the screwball plot – Locke and Geoffrey Lewis are guilty of some truly unforgivable mugging, and by proxy Eastwood is guilty of letting them mug.

“Bronco Billy” is always charming, but never quite substantial enough – or funny enough – to justify itself. It’s nice to see Eastwood spoofing his image at a time when that was still kind of a gutsy thing to do, and you can feel his affection for this trifling little tale throughout, but affection isn’t really enough gas to get a movie across the finish line. I smiled at a lot of “Bronco Billy”, and chuckled a lot, but I also (metaphorically) checked my watch and felt like the whole thing was a bit too relaxed, too dashed off. At his best, Eastwood’s films are laser focused and without frills; at his worst, Eastwood’s movies can have a hastily sketched feeling to them, as if he didn’t want to waste the time to get another, better take. Too much of “Bronco Billy” falls under the latter category; it turns “breeziness” into a bug. **1/2 out of *****

In a World (2013, d. Lake Bell) A vocal coach (Lake Bell) gets the opportunity to audition to be the trailer narrator for a series of films based on a popular fantasy novel…not realizing that her primary competition is her legendary voiceover artist father (Fred Melamed).

The feature directorial debut of writer/director/lead actress Lake Bell, “In a World” is a remarkably fleet footed little comedy. One would imagine it would’ve been easy for Bell to simply tailor a project that would act as a showcase for her specifically, and “In a World” does indeed work on that level: Bell is delightful as essentially a likable screwup, whose professional misfortunes are both a result of the prevailing sexism in the voice over industry (“it’s a man’s game,” her father smugly tells her, thinking he’s sounding sage) and, we sense, her own inability to get herself motivated enough to kick down doors. But Bell also shows enormous generosity to her large ensemble cast, all of whom are given funny, fun things to do. Fred Melamed is almost as good here as he was in “A Serious Man” – his superpower as an actor seems to be his ability to make boorish superiority likable (his character, Sam Sotto, is fairly awful, and yet impossible to hate); Demetri Martin is immensely charming as the sound engineer who harbors a crush on Bell’s character; and off in almost a separate movie, Michaela Watkins and Rob Corddry are just wonderful as Bell’s sister and brother in law, who experience their own marital crisis in the course of the drama – their storyline really has nothing to do with the central plot, but it adds a layer of emotional honesty to what could otherwise seem like “just” a farce. (Watkins gives perhaps the best performance in the movie, every expression a flickering fireworks display of nuanced emotion.)

Bell is clearly following in the footsteps of filmmakers like Woody Allen or Nicole Holofcener, creating a little pocket universe of funny characters and then letting them bounce off one another; even supporting players like Stephanie Allynee, Nick Offerman and Tig Notaro get memorable moments. (Alexandra Holden is particularly charming as Melamed’s much younger girlfriend, who turns out to not be the airhead we at first suspect.) The filmmaking is meat and potatoes simplicity, but Bell and editor Tom McArdle are attuned to the nuances of performance, and give the actors space to do their stuff. The result is a marvelous little movie. ***1/2 out of *****

The Pirate (1948, d. Vincente Minnelli) A young woman (Judy Garland) betrothed to the Mayor (Walter Slezak) of her provincial Caribbean village falls in love with an actor (Gene Kelly) she mistakes for a fearsome pirate.

“The Pirate” was something of a red headed step child for its makers. Producer Arthur Freed was in the midst of arguably the greatest run of musicals in the history of the American screen – the “Freed unit” at MGM created, among others, “Meet Me in St. Louis”, “On the Town”, “An American in Paris”, “Singin’ in the Rain” and “The Band Wagon” – and on “The Pirate” he’d joined three of his finest talents: dancer/choreographer Gene Kelly, director Vincente Minnelli, and Minnelli’s then wife, the dynamic Judy Garland. But Minnelli and Garland’s marriage was fracturing, and her drug use made her erratic and unreliable (MGM had essentially gotten her hooked on drugs as a young starlet, but that didn’t make them any more sympathetic when she wouldn’t show up to set). The erratic production resulted in a film that pleased neither critics nor audiences – “The Pirate” apparently was not the tremendous flop that history records, but it wasn’t exactly a moneymaker – and for most of the key participants it remained a wince inducing memory; Gene Kelly always spoke about it in measured tones, as an experiment that didn’t work.

“The Pirate” may not be the slam dunk masterwork that the best of the Freed unit musicals are; it doesn’t have the same seemingly effortless elan. But its neurotic undertones make it fascinating. The psychosexual undercurrents that normally only reared their heads in the dream ballets of other Freed musicals (think Cyd Charisse’s appearances as dangerously seductive femme fatales in the big ballets of both “Singin’ in the Rain” and “The Band Wagon”, or the way the relatively chaste love story between Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron in “American in Paris” explodes into something much more carnal during the titular ballet) is here a key narrative component. Judy Garland’s Manuela literally lets her hair down to perform the song “Mack the Black”, an ode to the vagabond pirate she hopes will spirit her away to a life of illicit adventure. On one hand the dynamic between Manuela and Gene Kelly’s traveling actor Serafin (who eventually poses as the reclusive pirate “Macoco”) reads as simply retrograde; like “Taming of the Shrew”, “The Pirate” could be read as a story about an uptight woman who needs to be shaken out of complacency by a “real” man, and some of the “jokes” veer into uncomfortable territory as Manuela talks about wanting a man to swoop down “like a chicken hawk” and grab her — basically, in ‘50s language, a rape fantasy. But that tension isn’t entirely unproductive – especially considering this is Judy Garland, who well into adulthood was still playing sexless teenagers (just four years earlier she was chafing at playing a high school girl in “Meet Me in St. Louis”; Minnelli had to chide her into not trying to “kid” her character), it’s rather startling watching Manuela’s eyes grow wide and her pulse visibly quicken as she watches Gene Kelly – who probably never looked fitter or sexier than here – dance his way through a dream ballet where, as a pirate, he lustily grabs maidens and murders opposing soldiers with a devilish grin on his face. The all American girl isn’t supposed to have these kinds of fantasies, and if she does, they’re supposed to stay fantasies, not explode in front of her with the fiery intensity of a supernova; there’s an extra erotic charge under much of “The Pirate”, an openly horny movie about people being dragged kicking and screaming into acknowledging their own unspeakable sexual impulses (both in front of and behind the camera – Minnelli was widely rumored to have been bisexual or closeted, and as Dan Callahan notes, the pirate dream ballet plays like Minnelli having his wife ogle his male crush for him).

As if sensing that they’d steered into thematically choppy waters, Freed and Minnelli seem to have compensated by playing most of the movie as farce. It’s a choice that has divided critics for years – Garland and Kelly are both playing broad here, he basically giving a prototype Kevin Kline performance (did Kline see this before he played in “Pirates of Penzance”…?) with bugged eyes and squealing voice, and she equally aiming everything at the rafters. But the robust style of “The Pirate” strikes me as the right approach to the material – the sexual tension bubbles under the surface, and every time it threatens to overwhelm matters, the film explodes into another bit of broad slapstick, another bit of hammy theatrics, or another bit of robust, wonderful dancing that relieves the simmering tension. The songs by Cole Porter are only so-so (although at least one song – “Be a Clown” – was good enough for producer Arthur Freed to more or less directly plagiarize it as “Make ‘Em Laugh” in “Singin’ in the Rain”), but perhaps emboldened by Garland’s absences, Gene Kelly really seizes the day, becoming combination dancer and stuntman – his early showcase number “Nina” is as impressive as a show of athleticism as it is a piece of dancing, as Kelly vaults from wall to walkway, up to the rooftops and down to the streets again, in search of female companionship. (The penultimate number of the film features an equally athletic trio of Kelly and the incomparable Nicolas brothers.)

It’s all a show, ultimately, the movie seems to say; the film literally concludes with Kelly and Garland virtually breaking character and performing “Be a Clown”, as if pulling back the curtain to show us that all these roles we play – social, sexual – are just masks, masks that trap us, masks we can throw off, but masks, above all, that we should take delight in. **** out of *****

The Trip (1967, d. Roger Corman) A commercial director (Peter Fonda) takes an acid trip, hoping to work through his trauma.

Producer/director Roger Corman had pivoted from Gothic chillers based on Edgar Allen Poe stories (“The Masque of the Red Death”, “The Tomb of Ligeia”) into the modern era with 1966’s “The Wild Angels”, the film generally credited with starting the phase of “biker pictures” that would climax with 1969’s “Easy Rider”. That film cemented a new direction for Hollywood filmmaking, with two of Corman’s proteges (Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper) helping create a new cinema that threatened to leave both old Hollywood and Corman’s brand of cheerful schlock permanently in the dust.

You can actually see a surprising number of the seeds of the “New Hollywood” in 1967’s “The Trip”. Both Peter Fonda and Bruce Dern returned from “Wild Angels” (Peter Fonda here is essentially playing Corman, a likable but slightly square Hollywood type trying out drug culture; Bruce Dern is the buddy/dealer who agrees to sit with him during his “trip”), Dennis Hopper plays a hippie drug dealer (there’s a notable sequence where Corman shoots the passing of a joint around a room as one lengthy 360 degree pan; Hopper would borrow the same shot for a moment at a doomed commune in “Easy Rider”), and the script, after several aborted attempts by Corman regular Charles B. Griffith, was written by a struggling actor named Jack Nicholson. Nicholson had some experience with LSD; Corman himself tried the drug prior to filming, but described only a “pleasant experience”, not anything as profound or surreal as awaits his main character.

On the film’s initial release, distributor AIP insisted on tacking on an anti-drug disclaimer to the front of the film, and an optical effect over the final freeze frame to suggest a crack-up coming. Corman’s original, unedited film is more ambiguous. Drugs in “The Trip” are just a reality, particularly in counter culture LA; sometimes you have a good trip, sometimes you have a bad trip, sometimes you do too much (there’s a scene where Luana Anders plays a sympathetic waitress who warns Fonda’s character about getting out of control while he’s high), sometimes you arrive at important personal revelations.

“The Trip” is surprisingly engaging, considering it’s not so much a story as an extended montage. Peter Fonda’s character drops acid, and the rest of the film basically flits in and out of the fevered visions inside his head. Those visions are cleverly set up by the film’s opening shot, where a kissing couple in a perfume commercial are revealed to literally be walking on water. It’s a surreal image, but also slightly kitschy – Hollywood surrealism, in effect — and the fact that this is the kind of image the Fonda character creates as part of his “day job” perhaps prepares us for the dreams he’ll experience on his LSD trip, dreams that walk a line between startling surrealism and kitsch cliché: figures running over white sand dunes, women morphing into and out of one another (during a sex scene, Fonda imagines himself having sex with both his ex-wife and a girl he has a crush on), a carnival merry go round.

“The Trip”’s biggest liability is Peter Fonda, who is somehow simultaneously wooden and over emphatic. Scenes where actors play high are always tricky – there’s a very thin line you have to walk between communicating the experience of being on a high and just acting silly – and Fonda unfortunately plays most of his scenes with Dern like he’s acting in a corny Christian anti-drug film (Dern in contrast is nicely and unusually understated here: he’s a conscientious friend who wants to make sure his friend has as “good a trip” as possible). Fonda may be a bust, but Corman surrounds him with enough visual tricks to mostly make his presence non-fatal. As shot by Archie R. Dalzell and edited by Ronald Sinclair (with Dennis Jakob given special credit for montage sequences), “The Trip” is inevitably dated – many of its “far out” effects now feel corny – but there are sequences where the imagery really does become hallucinogenic, arresting, hypnotizing. This 82 minute film plays like a piece of visual progressive rock – meandering in places, but now and then hitting an aesthetic fever pitch that is undeniable. The final five minutes or so – a montage sequence cut so ferociously that it puts to rest the notion that “fast cutting” is some kind of modern phenomenon – remain rather breathtaking. *** out of *****

THIS WEEK! A BONUS BOOK REVIEW!

“Funny Man: Mel Brooks” by Patrick McGilligan

Biography of the celebrated comic writer, actor and filmmaker.

Mel Brooks is almost always “on”. This is attested to in “Funny Man” by both his friends (like the late Carl Reiner) and family: even with many of them, we learn, Brooks is always performing. Very, very early in his life and career – when he was still a virtual nobody, back in the days when he was working as a kind of combination writer and “stooge” on Sid Caesar and Imogene Coca’s pioneering sketch show “Your Show of Shows” – Brooks had created a theme song for himself, which he would frequently perform upon meeting people: “Here I am, I’m Melvin Brooks/I’ve come to stop the show/I’m just a ham who’s minus looks/But in your heart I’ll grow/I’ll tell you gags, I’ll sing you songs/Just happy little snappy songs that roll along/Out of my mind/Won’t you be kind?/And please love Melvin Brooks.” He would end on bended knee, partly hectoring and partly begging the listener to laugh, with a combination of bravado and neediness that would come to characterize much of his professional comedy. Mel Brooks will do anything for a laugh.

Patrick McGilligan’s “Funny Man” attempts, as best it can, to pull back the curtain, and reveal something of the man behind the public “Mel”, the performer who has never exactly been a versatile actor but who, in on-stage and talk show guest appearances, has created a persona as distinct as those of the classic movie comedians – Uncle Mel, the wizened Jewish Uncle who will joke about any subject, not matter how outre, but who is basically a sweet guy who loves to sing and dance. Some reviewers have described “Funny Man” as a demythologizing book about its subject: “unflattering” was the word used in Entertainment Weekly’s review. I don’t know that “Funny Man” makes Mel Brooks “look bad”, but it does make him look like a human being, which apparently is equally disturbing for some, who don’t want their mythic characters clouded by human frailties. So yes, Mel Brooks had (by all accounts) a successful and loving second marriage to Anne Bancroft; but he also had a difficult first marriagewhich produced three children whom Brooks appears to have spent a fair amount of time working not to pay for. (To the reviewers feigning astonishment that Brooks would say unkind things about his wife in court proceedings: glad to know you’ve never met anyone who’s been through a divorce!) Brooks could be difficult and demanding on set – especially on his early films, he was a notorious screamer – but he could also be an extremely generous collaborator (on the set of his first film, “The Producers”, Brooks apparently clashed mightily with star Zero Mostel – a big ego himself – but appears to have made more than ample space for co-star Gene Wilder, then at the beginning of his career, and no doubt benefitting from Brooks’ considerate kid glove approach). As much as he could hold grudges, he also, according to McGilligan, “never forgot a mitzvah” – one of the more touching themes of the book is the way that Brooks would continually work to find parts for his former boss and mentor Sid Caesar, even as Caesar himself carped about having been “replaced” in the view of the public by his upstart apprentice. (The sense one gets is that a number of the other performers and writers who made up the members of “Club Caesar” had a mildly contemptuous attitude to Brooks, who was more of a ”talking comic” than a 9-5 writer; maybe that attitude helped instill an inferiority complex in Brooks, a desire to be more outrageous, more un-ignorable.). “Funny Man” presents Brooks as unique in certain respects, but in others fundamentally like most people who become wildly successful in show business: talented? Yes. Egotistical? Sure. Simultaneously unfeeling and deeply empathetic? Sometimes both within the space of a page.

Patrick McGilligan is for my money one of the best show business biographers currently working (he’s written wonderful books about Alfred Hitchcock and Fritz Lang, among others), but there’s often a curious detachment to his work. By his own admission, McGilligan writes biographies because it’s his job; unlike fellow Wisconsinite Joseph McBride, who wrote essential tomes on his favorite filmmakers (Steve Spielberg, Frank Capra, John Ford), one doesn’t always have a sense that McGilligan is particularly passionate about his subjects – they’re commercial ventures for him, and he approaches them with a coolly objective rigor. Sometimes this shoots the books in the foot: McGilligan’s expansive biography of Clint Eastwood, for example, is worthwhile as a corrective to so much of the fawning, sycophantic stuff written about Eastwood, but it's also a frustrating book in that McGilligan not infrequently seems to not only not like Eastwood, but be utterly baffled as to why anybody would. Curiously enough, McGilligan actually seems to warm up to his subject in the case of “Funny Man”; there’s a sense reading the book, as Brooks ages and mellows, that McGilligan can’t really begrudge Mel his exaggerations and fabrications, and that he has to give it up to the guy for writing a fairly spectacular third act – producing an incredibly successful Broadway version of “The Producers” in the 2000s, becoming a beloved elder statesman of comedy, and doing his best to make amends to some of the feet he’d trampled in earlier years. (McGilligan’s tone is perhaps tempered as well in the latter stretches of the book by the fact that Anne Bancroft’s death clearly took the wind out of Brooks’ sails; the anecdotes about the normally hyper Brooks despondent and down hearted are touching.) The public performance of “Mel Brooks” has been an ongoing concern for nearly 100 years now, and while that performance is sometimes tasteless (the book rightly takes Brooks to task for some of the homophobic humor in his films, which has not aged well), the enthusiasm is hard to deny. “He’s Mel Brooks all the time,” Brooks’ friend Noman Lear is quoted as saying, “but I can’t say that without saying he’s funny. He delivers.” **** out of *****

NEXT ISSUE: A modern fantasy classic, Alex Garland on the way we live, and Sidney Poitier in the director’s chair. Stay tuned.